For many, the idea of drinking sake conjures up the memory of throwing back a small cup of hot, overly alcoholic, jet fuel-like liquid served in a white porcelain tokuri at their local sushi restaurant. And, it wasn't necessarily a pleasant experience, even if you did happen to catch a buzz. This foray into unexplored alcoholic beverage territory rarely sent people running to their liquor store to buy sake to drink at home.

Fortunately, along with the recent growth in popularity of Japanese restaurants has come a corresponding increase in more sophisticated sake selections. Premium sake are now available by the glass and bottle at many of the new-style Japanese restaurants geared toward attracting the general population... and guess what? Thanks to this opportunity to try chilled sake, people are discovering the captivating aromatics and flavor profiles of these higher grade brews. “Wow! This is sake???” they say, “I’d love to buy a bottle of this!” So off to the liquor store they go...

Now the fun begins!

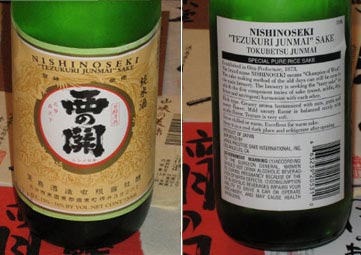

Sake labels contain a wealth of information. Most of that information however, is in Japanese characters which aren’t so easily decipherable. Many importers are working with the breweries and distributors to include English language translations of the basic essential information, usually found on the back of the bottle. When starting to make sake buying decisions, the natural place to begin is by identifying the sake’s grade or classification. So, let’s get into how sake are classified...

The rice used for making sake, sakamai, is grown specifically for this purpose and is different from table rice. In general, it is 25% larger, higher in starch, and has that starch more concentrated in its core or shinpaku. Starch is the most highly prized element of the sakamai since it is the source of the key component in sake brewing...but, we’ll get to that a little later.

In the first step of the sake making process, proteins and fats which make up the outer part of each grain of rice are milled (or polished) away to reduce or eliminate the undesirable aromas and flavors that they produce in the sake during its fermentation. It is the degree to which the outer portion of each rice grain is polished away, known as seimaibuai , that determines the basic grade and implicit quality level of the sake. The general rule-of-thumb is that the more highly polished the rice, the greater the complexity, fragrance, overall quality, and price of the sake.

These rice polishing-based grades apply exclusively to special designation tokutei meisoushu or premium sake, which represents only about 20% of all sake produced. The remaining 80% known as table sake or futsu-shu has no minimum rice polishing requirement. But, since we want you to drink only the “good stuff,” we’ll focus on premium sake classification.

There are two basic types of premium sake:

Junmai-shu – “pure rice” sake which is brewed using only rice, water, koji, and yeast.

Aru-ten – sake is brewed using rice, water, koji, and yeast with a small amount of distilled alcohol added.

Why the two approaches? As noted in Understanding Sake, over the centuries of sake brewing there has long been tweaking and experimentation to enhance aromas and/or flavors. Kuramoto (brewers) found that by adding a small amount of distilled alcohol at a critical point in the brewing process, they were able to produce more flavorful and fragrant sake. It is also said to give it a more robust structure and a bit longer shelf life.

Does this make aru-ten better? Ahh! That depends on how you like your sake! There are those purists who object to this approach and say that only junmai-shu is “real” sake. To add or not to add alcohol is a contested point in the industry and you will find that there are brewers who pride themselves on making only “pure rice” sake. In the end, we believe there is room for both since variety benefits sake drinkers by it giving us more choices and more different sake to enjoy! Each type of sake has three grades based on rice polishing minimum requirements.

Left: Genmai (unpolished)

Right: Daiginjo Sakamai (milled down to 35%)

These grades are the basic classifications but, there is one more important term to understand when it comes to sake classification. Tokubetsu, which means “special,” is a vague modifier used to indicate the use of either a more highly milled rice than the basic classification minimum or a special type of rice. It is usually used by brewers for Junmai or Honjozo sake made from rice that has been milled to Ginjo levels but for their own reasons (there’s that vagary) , have decided not to designate it as Ginjo, but rather Tokubetsu Junmai. Unfortunately, the bottle information most likely won’t tell you exactly what is “special” about what is inside. But, if you happen to be at Sakaya, just ask us and we’ll probably most likely have the answer.

Have a look at the photos to the right. Notice the difference between the unpolished and the daiginjo rice? You can clearly see the shinpaku in the daiginjo sakamai.